Grace Presbyterian Church

October 13, 2019, Pentecost 18C

Jeremiah 29:1, 4-7, 11; 2 Timothy 2:8-15

Where You Live

In last week’s scripture, Psalm 137, we encountered an unvarnished portrait of grief, sorrow, and even rage penned from the perspective of one who had witnessed and possibly been carried off in the Babylonian conquest of Jerusalem and exile to that despised empire. We heard of course sorrow and even rage and burning desire for revenge upon those who had carried out the destruction of Jerusalem, the Holy City itself.

Today’s reading from the prophet Jeremiah comes from a long discourse directed for the most part to that same community; those who had been carried away into exile in Babylon, as we are told right there in the first verse of Chapter 29. Had we read verses 2-3, we would have been given a list of names of leading figures of Jerusalem who had been among those carried off into that exile, as if to confirm that Jeremiah knew exactly who he was talking to and exactly what their situation was. The prophet was going to leave no room for misunderstanding; this message, from God, is for you, there in Babylon.

It was probably important to make this clear, since the message Jeremiah was delivering here is one that his audience in exile absolutely did not want to hear one bit.

Since reading three or four chapters and then delivering a sermon on them seemed unwise, a little bit of context is warranted. Much of Jeremiah’s proclamation to Judah, both those in exile and those left behind in ruined Jerusalem, was one of those proclamations prophets were wont to give, and their hearers were wont to dislike: this is on you, you know. The prophet was incessant about reminding the people that their own infidelity, their constant turn to the idols and false gods of the peoples around Judah, planted the seed that blossomed into this disaster. Crying out for deliverance to the God the people had abandoned repeatedly and consistently was pretty rich, and Jeremiah didn’t hesitate to make that clear to the people of Judah. And let’s face it; nobody likes to hear this kind of thing, especially the more true and correct it is.

Another factor in the context of this message is that Jeremiah is not the only prophet speaking to the Judeans in exile. Among the number of those taken off to Babylon were in fact several prophets, particularly those who had been well-attached to the important people mentioned in verses 2-3. You might refer to them as “court prophets,” as they had a kind of official status not only in the Jewish religion but in the state of Judah as well. At the same time a number of similar prophets had remained behind – not taken into exile but still performing more or less the same function in the conquered and ruined remains of Jerusalem.

Those prophets, unlike Jeremiah, were almost unanimous in prophesying a quick and painless return for the exiles from Babylon. Of course, these prophets had been quick to dismiss the idea that the people’s faithlessness would have any consequences; God was gonna protect Jerusalem no matter what because we’re God’s favorites. Never mind all that whooping it up with pieces of wood or stone and calling them your gods, God is gonna step in and protect us no matter what. Of course, that hadn’t quite worked out, but that didn’t stop this particular batch of court prophets from doubling down on their failure and insisting that this would not last long; in fact one of the prophets in Jerusalem, a man named Hananiah, insisted that all this foolishness would be over and the exiles would be back within two years, tops. It was this kind of false prophetic stuff that Jeremiah was called out by God to rebut and denounce.

Actually, Hananiah makes a rather dramatic case study of the way those false prophets worked. Chapter 28 tells the story of how Hananiah came out with one of his prophetic statements, with the two-year window and all, directly to Jeremiah, and the scene is the kind of thing Lin-Manuel Miranda might set as a big rap battle in the mode of the cabinet meeting scenes from Hamilton. Now Jeremiah was something of a melodramatic fellow; he had taken to wearing a yoke on his neck and shoulders as a representation of the heavy yoke that was placed on the people of Judah by the Babylonian conquest and exile. When Jeremiah responded to Hananiah’s prophecy with, roughly, “I’ll believe it when I see it,” Hananiah took the yoke off Jeremiah’s neck (which couldn’t have felt good) and broke it before all those who were witnessing this prophetic battle. The Lord then instructed Jeremiah to tell Hananiah how wrong he had been and how bad the consequences were going to be both for the people of Judah and for Hananiah himself, and Jeremiah threw in that Hananiah wouldn’t survive the year. Sure enough, Hananiah was dead two months later.

All of this goes to emphasize that not only was Jeremiah proclaiming a message not in step with the prevailing prophetic current of the moment, not to mention out of step with what his hearers wanted to hear; Jeremiah was also doing this from a position of lesser status, an outsider to the power elites of Judah (such as they were at this point). Never mind how right he had been leading up to the conquest and exile; nobody liked him and nobody wanted to hear what he had to say. Power and influence were not his by any stretch.

Therefore, when Jeremiah came forward with the oracle recorded here in Chapter 29, what sounds so lovely and encouraging when picked and chosen as the lectionary does actually sounds pretty awful to those to whom it is directed. Build houses? Plant gardens? Here? In this godforsaken place? Get married, and marry off the kids? Are you nuts?

Now in verse 10, which we did not read, God delivers through Jeremiah his own timetable for the return of the exiles. However, it wasn’t (to the people) a terribly welcome one; the exiles would return only after seventy years. Seventy! How many of the exiles would even live that long? And then God has the audacity in verse 11 to say that he has plans for the people, for their good, even, a future with hope. Hope? Hope for after I’m dead?

Well, yes, hope for after you’re dead. Jeremiah’s oracle is, after all, not to any one individual. He is speaking God’s message to the whole people of Judah in exile. Build houses, and live in them, plant gardens and eat of their fruit, have families. How is that hope? Well, if the people in exile don’t do those things, will there be any people of Judah to return to Judah after all?

And let’s face it; the fact that the instructions that Jeremiah passes along are even possible says something about the situation of the exiles. They are in exile, and they are cut off from all they have known at least physically; they are in an unfamiliar land away from the comforts of home (given the religious infidelity of the people in advance of the conquest and exile, the strange temples and shrines around them should not be that much of a shock). But they could build houses. They could plant gardens. They could marry and raise families. They could live. And God told them to live. God also told them not only to live, but work for the success of the icky alien city in which they were to live. This is your hometown now, God says, you’d best work for its good, because your good depends on it.

There’s also another message going on underneath all this: don’t act like I’m not there. The people had become so accustomed to Jerusalem as the Holy City, the Temple as the seat of the Lord Most High, that they had fallen into the unwitting (or maybe even conscious) belief that God only lived in Jerusalem, only could be found in the Temple. The people needed to learn that being taken away from Jerusalem was no reason to talk about being cut off from the presence of God. God was still present to the people of Jerusalem, no matter how far from Jerusalem they were. In other words, the people of Judah in exile needed to learn God in a different way.

Take all this together, and there really is a message for us amidst all of it. Since I moved away from my hometown for good, I’ve not been settled in too many places. I lived about ten and a half years in Tallahassee (all but one of those with Julia) prior to a short stint in Lubbock, Texas, but only three years in West Palm Beach, four years in Lawrence, Kansas, and three and a half years in Richmond before coming here, where I’m about four and three-quarters years in. It’s hard to say that I’ve lived any one of those places long enough to feel like it changed out from under me, so to speak. I suspect it may be different for some of you. I’m guessing that there are some of you who have lived here for a very long time, and sometimes wonder if this is the same place you moved to. It’s possible to feel alienated in such a circumstance.

Christians have a tendency at times to react this way to the world. We are prone to lament the loss of an ideal time, say, when churches were full (but truthfully because it was socially mandatory to attend rather than for any great faith reason), when somehow everything seemed less crowded and less hurried in the world around us, and when everybody knew everybody (and everybody was alike, if we’re honest about it, which meant everybody was like us). It’s highly possible for churches to idealize and as a result fail to live in the world we live in, so to speak. We’re so past-minded that we’re no present good. We feel alienated and sometimes we proclaim that alienation proudly, in between yelling at the kids to get off our lawn.

The reading from Jeremiah doesn’t recommend that, and nor does today’s epistle reading. We have work to do, and work to do in order to prepare for that work. Our job, as this epistle reinforces, is to remain faithful, no matter the circumstance, to “endure everything,” and to prepare ourselves to give a good account of the Word we have been given. Our comfort in the world or the degree to which we feel like home isn’t a factor in our call. Minister anyway.

Minister anyway, and remember that no matter how much we might feel cut off or homeless or generally out of sorts, God is with us, leading us to keep living and calling us to remain faithful. You can’t ask for much more of a mandate than that, no matter where you live.

For the call to build and plant and live, Thanks be to God. Amen.

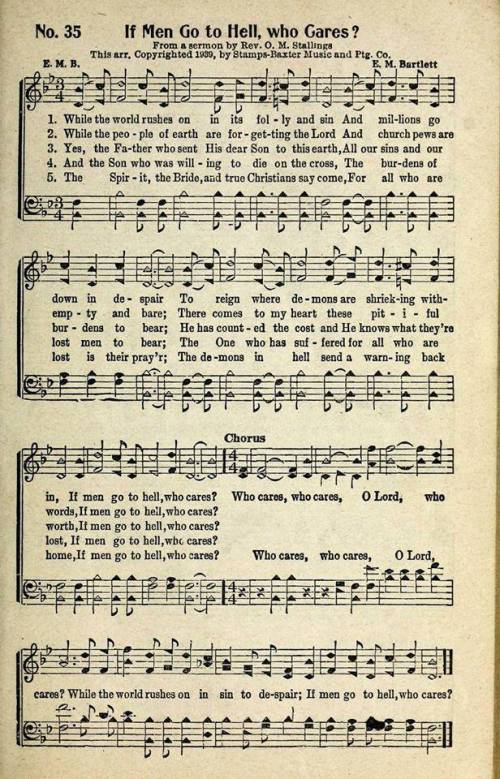

Hymns (from Glory to God: The Presbyterian Hymnal): #41, O Worship the King, All Glorious Above; #54, Make a Joyful Noise to God! (Psalm 66); #39, Great Is Thy Faithfulness; #351, All Who Love and Serve Your City

You must be logged in to post a comment.